Germany (1925 - 1939)

The Young Parents - Balzano 1927

The second child of Hans-Joachim and Josefine, he was delivered in the small hours of 21st April 1925, at the Marmor-Palais in Potsdam, where Frederick the Great had his famous colloquies with Voltaire, adorned his pleasure palace Sanssouci with floor tiles depicting the newly imported potato and exercised his acclaimed troops which put the fear of God into him as much as into his foes. Distinctly Prussian, with its simplicity, directness and moral contradictions; but a very different world from nearby Berlin. Closer at hand lay Neubabelsberg, site of the film studios where some of the books his parents would write together came to be filmed.

In noble families the custom was to honour both antecedents and godparents by bestowing on the child a long string of weighty forenames. His parents notably broke with this tradition - as with many others - christening him simply Hans-Joachim after his father, and David after his maternal grandfather. The latter had already embraced the Christian faith, but his name was still to bear heavily on the fate of the newborn child.

For the moment, there seemed to be few clouds on the family's horizon - aside from the disorders following the end of the Great War and the fall of the Kaiser, accompanied by rampant inflation. Pent-up social ideals, political inexperience and popular anger at a decade of war and useless sacrifice proved ready to be exploited. By the time the boy was eight, he would find the family on the wrong side of the new ideology - doubly so, as liberals and as 'racially tainted'. Two years later they faced his father's death from a brain tumour as a legacy of gas poisoning in the Great War, followed by the growing isolation of his mother and restraints on her means of livelihood.

'Non-Aryans' were denied the right to practise liberal professions. In addition to co-authoring books published in her husband's name, his mother wrote independently as an active social commentator. That, too, was denied. One of the boy's memories during his father's illness and following his death were visits from Herrn und Frau Wiegler, editor of the Ullstein publishing house, and his mother saying, "I can hardly believe it myself, but I have just found another of my husband's manuscripts. A lovely tale that is just begging to be published in memory of his name."

Writing was somehow already printed in the father's veins. His mother, by all accounts a formidable lady, impatient with the constricted life of a provincial garrison commander's wife, exercised her physique by rearranging the furniture, and her mind by the forbidden trade of writing novellettes under a male nom de plume. Her son made his name with a first published work of tales collected in a pre-World War I Nevada goldrush settlement, to which he had been inveigled by a malicious elder brother, a born gambler who had joined the rush with serious intent, then found he had no one to talk to. The younger brother, fresh from the isolation of the Guards Academy, discovered a life as chequered and dramatic as any novelist could wish. The squalor of the camp and the disillusion of the fragile souls who had strayed there in the expectation of easy riches engaged his sympathy, allowing him to look below the surface.

He at least came away enriched. Many years later, he confided to his young bride, "If anyone of my fellow cadets had told me I would end up as a brain athlete, I'd have knocked his teeth down his throat."

They had met when Josefine {'Pepi') Schoenfeld was fifteen, on the point of flowering into a ravishing beauty, and they promptly fell lastingly in love. To the dismay of their parents, who thought them entirely unready to make such decisions, they regarded themselves as formally engaged. It was to take many years and a world war before they could be married, but their determination was only the first of many signs that they belonged to a new generation and held very different aims and ideals from the closed society of their forebears. They became the decent face of the social and political upheaval eventually to burst every bound around them.

As young adults, they took life seriously, especially that of their children. They were dedicated to a healthy lifestyle, where every pleasure was weighed in relation to its impact on body and mind. That made for a bounteous childhood, with an abundance of fresh air and even fresher fare. Exercise was not imposed but came in frequent excursions into the surrounding forest, to discover dewy-nosed creatures grazing shyly in sunflecked clearings and other wonders of the natural world. There were the manifold waterways of the Havel river, where the boy learned to swim - by the simple expedient of losing his footing and the stark choice of sinking or doing it.

With time, the house in Babelsberg became increasingly conspiratorial. Finette (Josefine Charlotte), his elder sister, was a lovely and wondrous child, but essentially withdrawn.

It may also have accounted for Finette's fierce protectiveness of her younger brother and his foibles. The affection between the siblings was profound, even if prone to sudden squalls, heightened by the growing sense of insecurity from the world outside. Finette still maintained a circle of friends, shrinking as did her mother's, as families emigrated, or simply disappeared. Eventually it became concentrated on a young man to whom she became engaged, and remained so despite the family's enforced separation, until the outbreak of war ruptured that relationship, like so many others.

The risks of allowing children into other people's homes had further restricted social life. The consequences of children's babble could be existentially dire. A totally innocent remark might be reported by zealous companions converted to believing it their duty to help root out 'opponents of the State'. That same fear cut short his musical training, abandoned after piano lesson one.

Elementary school under the guidance of Herr Brinkmann brought new discoveries in rapid succession. It seemed as if for the first time the boy was drawn into an active part in opening new swathes of knowledge. He continues to be remembered with profound gratitude for his abiding influence.

With advancing racial indoctrination, later schools proved less welcoming. From bullying to class protests, one after another had to be abandoned. A kindly memory has engaged selective recall to obliterate the less agreeable episodes. The three years to age 13 were punctuated by at least four different schools. By no means all his fellows were unfriendly, the more so as schools were coeducational and his awareness of girls was coming alive. Looking back on it, it was an uneasy, vaguely exciting time, whose full menace mercifully remained obscured in the general uncertainties of adolescence. These were mirrored most blatantly in the heterogeneous society of Berlin, the traditional meeting ground of nationalities, cultures, sins and pleasures unbridled.

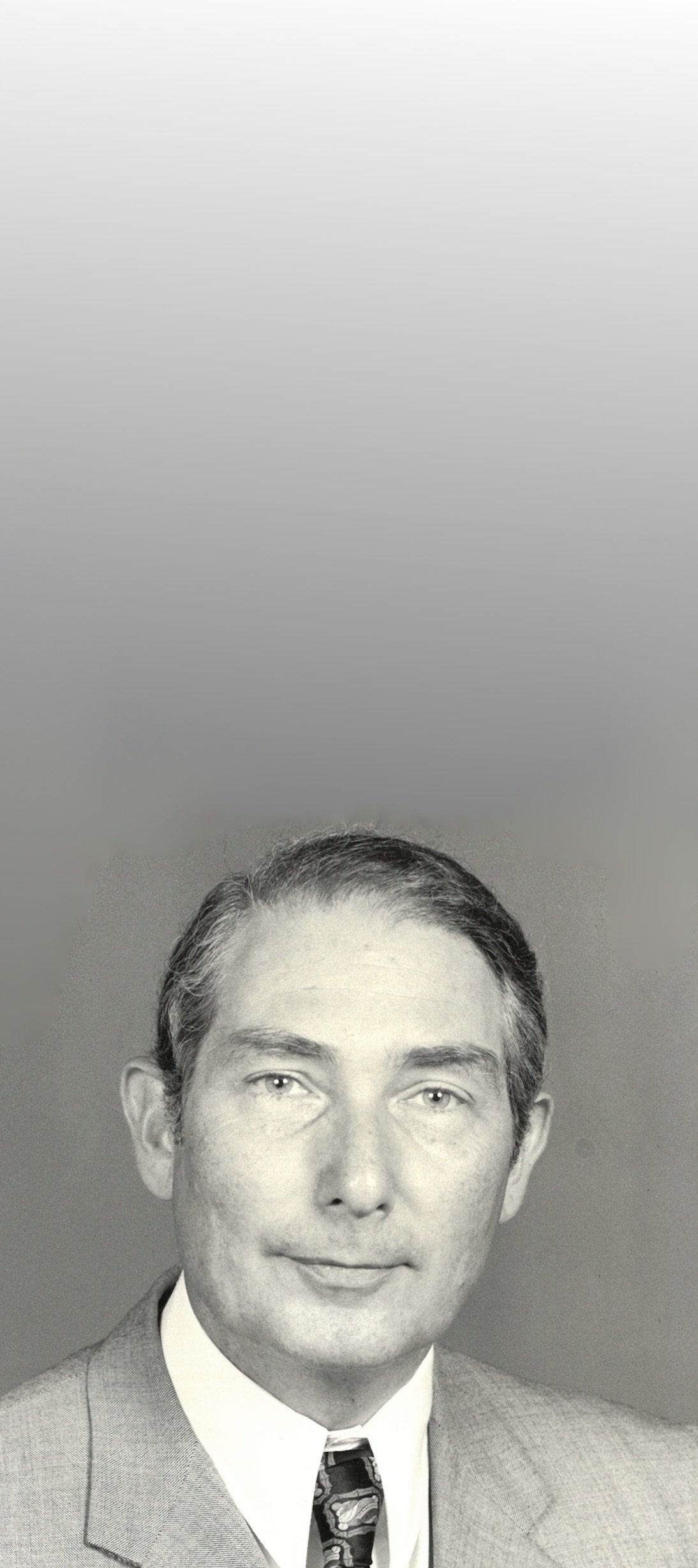

Father and Son

Leaving

By early 1938 much of the world was aware of the savagery of the Berlin regime, its abjuring of large sections of its citizenry and the death sentence passed upon them. Concentration camps housing 'undesirables' had multiplied and, though foreign governments were still reluctant to acknowledge them, death camps were being developed on an industrial scale.

Civil society in the western world had begun to respond to the plight of those condemned to be slaughtered. There were the Kindertransporte, organised for the most urgently affected, which assembled trainloads of children delivered by their endangered parents without knowing their destination, certain only that they would never be reunited. Whilst governments remained aloof, the staff in some Embassies were moved spontaneously to exercise greater leniency with applications for visas which they knew would save lives.

One of the best considered initiatives was that organised by Bishop George Bell of Chichester. His Committee trawled public schools throughout Britain that would award free places to refugee children, which in turn asked parents of their pupils to provide a home. An office in Berlin's Tiergarten established the link. The boy's mother had quietly gone there as soon as he entered his fourteenth year, critical because on their fourteenth birthday all boys had to join the Hitler Youth for indoctrination. As a mixed-race 'Mischling' he would not be admitted and would therefore publicly become a misfit.

The Committee quietly initiated its work, and a few months later signalled the desire of a visit by a Major Lawrence A. Leech to Babelsberg. There entered a tall, kindly man of relaxed military bearing, who seemed as embarrassed as the family greeting him. It was not done to show one's feelings, and Englishmen were said to be particularly reserved. The surroundings in which he found himself must also have been confusing. Charity is automatically related to poverty, of which there would have been few signs. Yet here was a need even more stark, but expressed in other terms against an apparently well-to-do background. It spoke volumes that a desperate mother and a complete but well-intentioned stranger were to find a quick rapport.

As Managing Director of an engineering company, Major Leech had occasion to visit Germany on business, to study road building techniques. The first meeting, clearly a fact-finding reconnaissance to discuss with his own family, appeared to have been satisfactory. Some months later, he would come by to discuss the detailed arrangements. Plans were made for the boy's travel and reception in Croydon, both in the Leech household and in the nearby school called Whitgift (also after a former Anglican Bishop). In Babelsberg, the house had to be sold to provide a 'dowry' for Finette and to pay the large sums demanded for an exit visa; mother would have to exist on the rest. That entailed a move to a rented flat in Berlin. For the boy, coming from the sheltered walls of suburbia, the sight of a metropolis and its fevered pulse proved a merciful masking of the grimness of the underlying facts. There were sights, aromas, customs, events, entertainments, behaviours, unnamed temptations and illicitness, all accentuated almost frenetically by the perils of living in a society without laws or mercy. The boy and that society were infected by the same need to escape the realities of a daily life that could be ended by the whim of any official - a danse macabre on a metropolitan scale.

At last, the myriad arrangements and formalities surrounding the boy's departure were in place and all seemed set for a final parting. The mother appeared stoic in the face of the double fate of sending away her son and being left solitary before an abyss devoid of hope. The same thoughts appear to have been debated in Croydon, at the same moment. With only ten days to go, the voice of Florence Leech came over the phone and said, "We cannot bear the thought that we are taking your son away from you, and leaving you to your fate." And then, "So we thought, if you would like to come over with him, we could arrange for a visa. And you could stay with us for a few weeks until you found your feet."

And so, on 27 April 1939, less than a week after his 14th birthday, mother and son were welcomed by the Leechs at Croydon Airport - she with the numbed joy of literally a stay of execution, he with the excitement of a first-ever flight, on a Dornier which, before long, would revisit London to drop its murderous munitions.